Lupine Publishers Group

Lupine Publishers

Menu

ISSN: 2690-5752

Review Article(ISSN: 2690-5752)

Love Scenes-Unfinished: A Critical Enquiry into Modes of Representation in Scenes of Love and Sexuality in Western Art Volume 7 - Issue 5

Dr phil Iris Julian*

- Margherita von Brentano Zentrum, Freie Universität Berlin (FU), Austria

Received:January 17, 2023; Published: February 14, 2023

Corresponding author:Dr phil Iris Julian, Gutachterin: Margherita von Brentano Zentrum, Freie Universität Berlin (FU) Währinger Straße 156/16 1180 Wien Österreich, Austria

DOI: 10.32474/JAAS.2023.07.000272

Abstract

Depictions of love and sexuality in Western cultures: as art historians have shown, the dominant mode of representation entails an asymmetry that emerged during the Renaissance era. Since then, ‘women’ have been depicted as corporeally present, while their ‘male’ partners have been incorporeal, therefore representing immaterial entities – for example, Jupiter disguised as rays of light, clouds or rain. In my ongoing research, I have found that the incorporeal man/corporeal woman structure remains the prevalent manner of representing male-female love scenes, both in the (self)representations of ‘female’ artists and in depictions of their ‘male’ colleagues. To discuss this asymmetry, I employ an interdisciplinary approach combining art history, dance studies and visual culture. I outline a twofold perspective: a diachronic perspective based on art history and a synchronic perspective of the contemporary dance field with its dance markets and institutions. My analysis is intended to provide a background for the search for alternative forms of representation in contemporary dance and performance.

Keywords:Modes of representation of love; sexuality scenes in contemporary dance; performance

Introduction

Is there a direct causal link between the representation, or visibility of people in the ‘female’ category and a stronger political presence? In other words, does the self-representation of ‘women’ necessarily improve access to privileges? According to cultural scientist Johanna Schaffer, who argued that every form of visibility conveys ambivalences, the assumption of a causal relationship between visibility and political presence, or power and privilege, can often be found in feminist, anti-racist, queer-feminist and activist groups. As she writes, although the topos of visibility has become a central category in oppositional political rhetorical practices, visibility should be handled with caution, as the visual field is informed by highly complex processes between giving-tosee, seeing and being-seen [1]. Schaffer’s arguments opened up a discussion that I will outline here in relation to the theme of love and sexuality. The way in which this theme is represented by artists will function as my lens for highlighting the ambivalences that stem from the (self)representations of artists being said to belong to the category of ‘women’. When I examining media reports on contemporary stage performances, I noticed that ‘female’ artists performing nude is commonly interpreted as a feminist strategy [2]. The main argument is that ‘female’ artists dispose of their own bodies and are free to choose their artistic means and modes of representation instead of being staged by an artist or director in the ‘male’ category. This assertion may come as a surprise because in the 1990s, feminist theorists contested and criticized the notion of a direct causal link between being-seen and political empowerment. For instance, performance theorist Peggy Phelan opposed this notion by provocatively stating that if there were a causal relationship between visibility in the media and political power, we would be governed by young white, half-naked women [3].

Within art as activism, certain artists shared Phelan’s argument and opined in the same direction. The Guerrilla Girls, a joint venture of anonymous ‘female’ artists, critically questioned scopic regimes and orders of representation. When they launched their poster campaign Do Women Have to Be Naked to Get into the Met. Museum? (1989), they intended to inform passers-by that there is a stark asymmetry in art discourse and history. On their billboards prominently displayed in public spaces, they wrote that less than 5% of the artists in modern art departments in renowned museums were women, while 85% of nudes were ‘female’. They argued that although ‘women’ are depicted in pictures, especially when it comes to sexualised representations of the physical body, ‘women’ are not given the status of artists [4]. In this essay, I will ask whether it is precisely the connection between the nude body and ‘women’ that leads to the fact that people in the ‘female’ category tend not to be perceived as innovative artists and inventive minds.

Theoretical Implications of My Research

In recent years, theatre and dance studies in German-speaking countries have entered a phase of transition. Various scholars have engaged in a fruitful methodological discussion aimed at critically reflecting on the prevailing single-work-centred approach and creating interdisciplinarity via connections to other disciplines [5]. Writing this essay in the wake of these new tendencies, I combine art history and theatre studies to subsequently complement both disciplines with approaches from visual culture [6]. As art historian Tom Holert, himself an academic working in visual culture studies, explained, this direction understands cultural artefacts as active parts of communication. Accordingly, visual culture scholars place less emphasis on the meaning that a visual product conveys, such as its reference to a specific iconographic tradition, and seek, instead, to explain how pictures co-influence reality by shaping our perception processes [7]. In emphasizing the influence of images on social processes, Holert agreed with one of the best-known theorists of the Pictorial Turn, literary scholar W.J.T. Mitchell [8]. Understanding pictures as an active and implicit part of communication means that a representation (e.g. of certain groups of people) is more than just a ‘depiction’ because pictures shape our thinking and thus influence processes of recognition and/or devaluation.

Assuming that images affect their viewers, the question arises as to how one should theorise the way in which images and depictions co-influence us. This question foregrounds significant philosophical issues. Visual culture’s assumption that artefacts not only depict reality but also significantly shape perception goes hand in hand with non-essentialist and anti-foundationalist critiques, pointing towards epistemology and metaphysics [9]. Love and sexuality, the subjects of my study, require a critical theoretical background to effectively challenge the bipolar structure of representing the sexes. Although, in recent years, the book Gender Trouble: Feminism and the Subversion of Identity (1990) [10] by literature scholar Judith Butler has been criticized by posthumanist thinkers, her theory of repetition provides useful arguments for establishing a critical distance towards hegemonic patterns of Western thinking. Heir to thinkers such as film theorist Teresa de Lauretis, [11] who had already outlined the sex/gender division as an analytical tool in the mid-1980s, Butler conducted deep inquiries into the philosophical problem of the metaphysics of substance. As she argued, a coherent subject and a self-identical being should rather be perceived as effects of regulatory and repeatedly performed practices shaped by social norms, schemata and categories [12]. Using the theory of repetition, constraining patterns and perceptual grids can be deconstructed by approaching what essentialist thinkers conceive as substances as mere effects of repetitions that form discursive chains throughout human history.

As Butler writes, despite the existence of intersexual people, whose desire, sexual practice and biological ‘incoherence’ rather point to ranges of variations than bipolar sex/gender manifestations, philosophical discourse and scientific disciplines still rely on the twofold substance of anatomical sex and discursive gender [13]. Consequently, the multiplicity of sexualities is domesticated and narrowed down by language and its grammar and reduced to a Western bipolar system of sexes [14]. By drawing on Butler’s non-essentialist thinking, I perceive sexualities along a greyscale of variation. In other words, the theory of repetition provides me with a background for explaining how pictures co-influence us by maintaining narrow bipolar structures from one generation to the next. As I will discuss, the social world contains ideas belonging to coercive social structures that form hierarchical orders.

Non-essentialist thinking is the prevailing mode of reasoning in visual culture. Although language plays an important role in this research direction, the focus is more on pictorial representations. One of the first anthologies in this direction, Vision and Visuality (1988), was edited by art historian Hal Foster. In his preface, Foster outlined a conceptual structure that should become highly influential in cultural studies. More specifically, he distinguished between, first, vision and sight as a physical operation (that is, how we see) and second, between visuality as the level of theory (the way we understand and reflect on sight) and seeing, its discursive determination. According to Foster, not only do humaninvented devices, such as microscopes, television or mobile phones, transform seeing so that it becomes a cultural, non-natural practice, but the way in which we perceive is actually always informed by the culture into which we were born. In other words, we are already being-made – seeing on a pre-linguistic level. This assumption leads Foster to conclude that the gaze, or the seeing, is not innocent or ‘natural’. Therefore, the bipolar system of the sexes as conveyed through images and pictures is a pattern that we are trained to follow.

To outline my arguments, I will pursue Foster’s notion that seeing is linked to hegemony processes in the field of the visual, as scopic regimes produce mechanisms and dynamics that reduce variations and close out differences [15]. What is important here is that Foster also assumes that humans possess the possibility to open the vision that has been narrowed down. Through the lens of art history and dance and theatre studies, I will consider the traditions of depicting and the ways in which we are being-made-seeing. Then, in the second step, I will create a distance, an interstitial space, between what is given-seen and our understanding of what we perceive. Bringing together Butler’s theory of repetition and Foster’s concept of vision/visuality, I assume that the greyscale of ‘male-female’ variations is constantly narrowed down to only a few culturally dominant visions that are commonly understood in an essentialist manner.

A Starting Point with Birgit Jürgenssen

In 1976, Viennese artist Birgit Jürgenssen (*1949, † 2003) staged a series of black-and-white self-portraits using the medium of photography that showed her face while she was pressing it against a glass wall. As the glass modulated her facial features, the glass became visible, posing the question of what might be on the other side. The transparent surface of the material became an indicator pointing to that which remains invisible (but informs our non-natural gaze). From my position as an art historian, I perceive these photos primarily as a reference to the tradition of portraiture as inherited from the Renaissance – for instance, the self-portraits of Albrecht Dürer and Leonardo da Vinci. Not only is the traditional mode of depiction modified by the pressing of the face against the glass and distorting it, but there is also a further noticeable difference, namely a reference to an imaginary temporality. Jürgenssen, who took these pictures in the 1970s, put a lot of effort into her styling – for example, her hair is deliberately modelled on 1950s fashion, when she was a little girl in Austria during a time that was characterised by a post-war mood marked by the setback of traditional family values. The artist gave us a clue about how she read this photograph by providing a description above her photographic alter ego: ‘Ich möchte hier raus! (I want to get out of here!)’. In the context of other works by Jürgenssen, the series suggests a feminist reading. In her discussion of the series, art historian Gabriele Schor described Jürgenssen’s work as a critical commentary on the unpaid work of the housewife [16,17,Figure 1].

Figure 1: Birgit Jürgenssen, Ich möchte hier raus / I Want Out of Here! 1976, b/w photograph, 40 x 39,9 cm, © Estate Birgit Jürgenssen / Bildrecht, Wien 2023 / SAMMLUNG VERBUND, Vienna.

Using Foster’s vision/visuality distinction, it can be said that although there is no way out of the field of visibility, there is at least the possibility of loosening existing patterns by opening up inherited frames of perception. On the level of visuality, we can critically reflect on structures and on ‘how we see, how we are able, allowed, or made to see, or how we see this seeing or the unseen therein’ [18]. In this sense, Jürgenssen’s work is a strategy for establishing a breach in the hegemonic representation of ‘women’. Through her series, she poses questions and creates a critical distance.

By countering the widespread assumption in activist circles that visibility equals empowerment, Schaffer emphasised that every representation and every image enter a field of the visible in which inequality prevails. According to Schaffer, the field of the visual is determined by two modes that are closely interwoven and modulate each other: visibility and invisibility. She argued that some subjects are given more visibility and some less, while others are hardly or not at all intelligible; thus, the distribution of visibilities is highly unequal. Schaffer went on to claim that although there are some stereotypical representations that favour certain groups of people, there are also representations that lead to devaluations [19]. Therefore, even the best intentions are always at risk of involuntarily and repeatedly upholding the prevailing order. Working towards empowerment requires prior analysis [20]. However, which tools can provide us with a precise approach for analyzing the way in which the ‘female’ and the ‘male’ are represented? Based on the assumption that we are dealing with highly complex processes in the field of visuals, [21] Schaffer proposed several analytical tools. First, there is the question of who is given-seen and who remains invisible. Second, a precise analysis must entail information on the socio-political contexts in which a particular practice, process or work has been given-seen. The third tool, or level, of analysis involves the material realisation of what is given to be seen [22]. In short, the three basic categories that Schaffer proposed are who (is being seen) – where (in which contexts) is something given-seen – and how (does the materiality correspond to the sense of the work). For my discussion, I will focus on the first categories, namely who is depicted and in which contexts.

Another Starting Point with Mette Ingvartsen

In 2011, Danish choreographer Mette Ingvartsen premiered her solo piece Speculations, which was designed for a theatre stage. The whole piece consisted of a word choreography and storytelling, a mode that dance scholar André Lepecki referred to as an ‘expanded notion of choreography’ [23]. In Ingvartsen’s piece, some scenes do not have concrete reference points, such as dates or places, and are minimally outlined and not identifiable as an excerpt from a film, a book or realised performances. Other scenes, as the audience learns more details, become readable as excerpts from a specific work. The main characteristic of Ingvartsen’s artistic approach is that, by using words, she creates a difference between what we actually perceive and what we imagine. To accomplish this, she points to precise areas in the concrete space that she shares with her audience while telling a story. In this mode, Ingvartsen tells us about naked dancers covering themselves with thick layers of paint. After a while, this scene becomes legible as Yves Klein’s performative work Anthropometries (1960-1962) for which he employed ‘female’ models as living paintbrushes [24].

Inspired by Ingvartsen’s piece, I am proposing a rather unconventional dance theatre analysis by selecting, as Ingvartsen does, a scene suggestive of love and sexuality without naming its author, performers or title. I believe that by simply focusing on the how of the representation, one can avoid overemphasizing the importance of the singular, which makes the scene readable as a structure that can appear at different times and in different contexts. The non – essentialist view that I pursue brings with it a variety of implications-one key implication is the perception of artists not as individuals separated from their surroundings but as always influenced by various contexts. As will become clear in the following sections, inspired by the theory of repetition, I perceive artists drawing on structures that they encounter in art traditions so that a diachronic line evolves. Moreover, being embedded in specific contexts, networks and institutions, such as theatre houses and festivals, artists always refer to and work in a synchronic field.

Imagining myself being Ingvartsen, I would describe the following sequence: An empty stage, in complete darkness. After a while, a soft spot of light becomes increasingly brighter, and a person whom I recognize as being in the ‘women’ category enters the auditorium. She walks downstairs. She is wearing a furry dark, almost black coat. She walks through the auditorium and onto the stage, where she unbottons the coat, baring her body, and starts to cover her skin with white powder. The powder fulfils multiple functions: it makes her body features even shinier and more visible, reminding me of one of the famous paintings by Peter Paul Rubens; the white powder on her skin creates a sharp contrast with the dark surroundings of the theatre’s black box. The task of powdering herself is also a choreography of movements, which are sharp, short and rhythmic, in tune with the rhythm of the baroque music. With her body covered in white, she continues with the performance, touching herself, alluding to erotic scenes. Due to her movements, the powder starts spreading out all around her body again. In this scene, as so often in erotic dance, we do not find a partner, instead, a cloud of powder envelops her like an immaterial entity transcending her body-space. Fade out. This scene provides me with a starting point for discussing this image along both a diachronic line informed by art history and theatre studies and a synchronic view on the dance and performance scene.

Along a 500-Year-Long Timeline

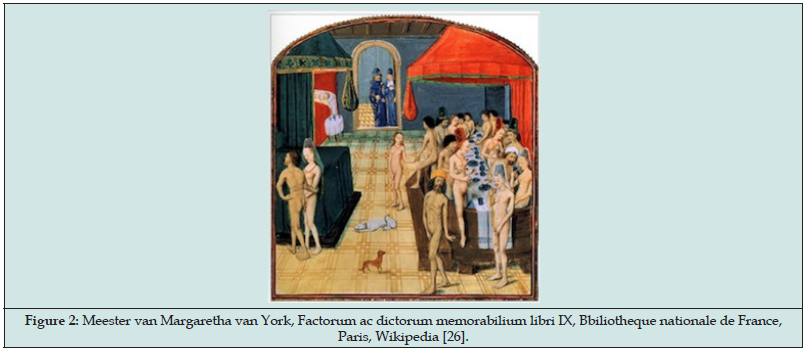

Figure 2: Meester van Margaretha van York, Factorum ac dictorum memorabilium libri IX, Bbiliotheque nationale de France, Paris, Wikipedia [26].

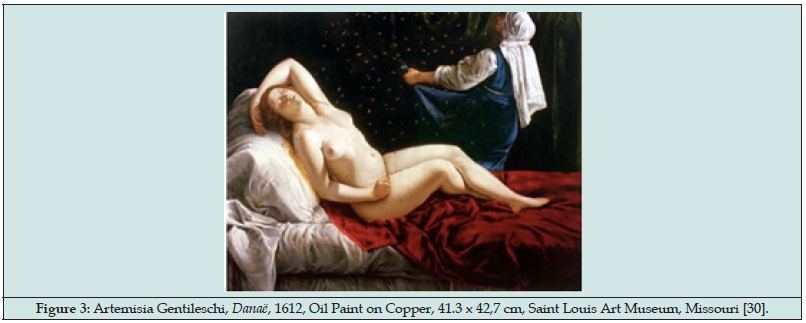

Figure 3: Artemisia Gentileschi, Danaë, 1612, Oil Paint on Copper, 41.3 x 42,7 cm, Saint Louis Art Museum, Missouri [30].

The erotic and highly sexualised scene I have just described, centred around the ‘female’ body while the ‘male’ body is absent, comes from a contemporary piece, but the structure of this representation – the ‘female’ being alone on stage, surrounded by a cloud that represents an immaterial principle – can actually traced back along 500 years in art history. Scenes of love and sexuality have been researched in depth by art historian Daniela Hammer- Tugendhat. While critically questioning representations of people in the ‘female’ category, she discovered an asymmetrical twofold structure: depicted ‘women’ are physically present, whereas the ‘man’ part remains absent. This structure, as she explains, only evolved, in the age of Renaissance, whereas in the Middle Ages both partners, the ‘male’ and the ‘female’, were represented in naked corporality. To give examples from the Middle Ages, she cites illustrations depicting people in bathhouses where the representation of both partners prevailed [25]. The illustration in Figure 2 that I cite in this essay comes from the Factorum ac dictorum memorabilium libri IX, a book written by the Roman writer Valerius Maximus (Biblothèque nationale de France, Paris), which was illustrated approximately in 1475 [(Figure 3), 26]. In this illustration, the idea of naked physicality is presented without being too explicit, as the walking motif of the ‘men’ serves to conceal their genitals, while the ‘women’ hide their primary reproductive organs with either their long hair or their hands.

Another scene that Hammer-Tugendhat mentioned in her studies is the love garden, which was quite popular in Middle Europe at the end of the 14th century and in which both partners were depicted [27]. At the beginning of the Renaissance era, modes of representation began to change, and images of love and sexuality were increasingly being created using the medium of oil painting on canvas or metal plates. According to Hammer-Tugendhat, as these paintings emerged in a Catholic society, which was coerced and intimidated by the inquisition, images depicting love and sexuality could not be too explicit [28]. The patrons of these paintings, who had undergone a certain education because they came from higher nobility, found a way of concealing the actual theme of love and sexuality by drawing on stories from ancient Greek mythology found in the Metamorphoses by the Roman poet Ovid [29]. It was, above all, the adventures of Jupiter – who appeared to his beloved Danaë as rays of golden light and melted into a rain of golden coins, transformed himself into a cloud that enveloped Io (against her will) and approached Leda in the guise of an airy swan – that made it possible to conceal the actual act of love, the coitus. In each scene, the father of the gods was represented as an immaterial entity. The depictions in Figures 4 & 5 show the love scene of Jupiter and Danaë as painted by artists from both the ‘female’ and ‘male’ categories. Figure 3 contains a painting by Artemisia Gentileschi (*1593 in Rome; †1654 in Naples), and Figure 4 shows a somewhat earlier Danaë by Titian (*c.1490 in Pieve di Cadore; †1576 in Venice). According to the narrative mentioned by Ovid, [32] the ‘female’ part, Danaë, is in her dark prison chamber, lying in full naked physicality on her bed, immersed in dark brown hues, while a ray of light and golden coins – Jupiter – fall from above, slicing the darkness of the chamber, setting a rhythm and touching Danaë’s skin. Jupiter’s appearance as a ray of sunlight, becomes readable as the equivalent of the warm hand of a physical body.

Figure 4: Titian, Danaë, 1560/65, Oil on Canvas, 129.8 x 181,2 cm, Museo Nacional del Prado, Madrid [31].

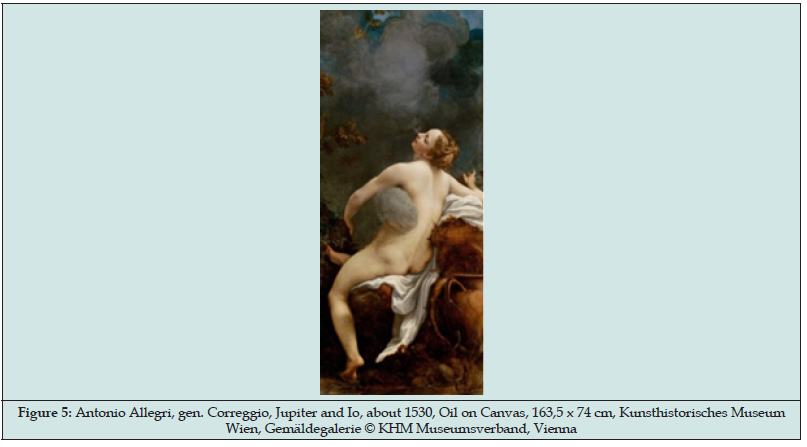

Figure 5: Antonio Allegri, gen. Correggio, Jupiter and Io, about 1530, Oil on Canvas, 163,5 x 74 cm, Kunsthistorisches Museum Wien, Gemäldegalerie © KHM Museumsverband, Vienna.

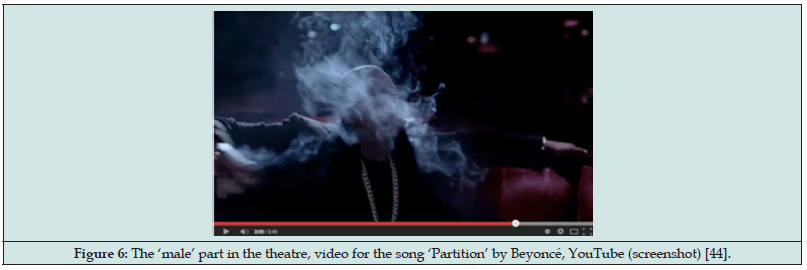

Figure 6: The ‘male’ part in the theatre, video for the song ‘Partition’ by Beyoncé, YouTube (screenshot) [44].

A further story of Jupiter’s innumerable love adventures is the story of Io, which was also found in Ovid’s Metamorphoses [33]. Like most painters who depicted this story, Antonio Allegri da Correggio (*c.1489 in Correggio; †1534 in Correggio) focused on the moment when Io is caught by the god as he envelops her in a dark cloud. It is basically a scene of rape and aggression, softened in the mannerist style by the women’s elegant posture, while Correggio plays with her long neck, the style of her hair and the soft tones of her skin.

As Hammer-Tugendhat pointed out, the physical equality between the ‘female’ and the ‘male’ parts of the love act found in representations in the Middle Ages is broken in these paintings. From the Renaissance onwards, the predominant structure in the scenes of love and sexuality involves an asymmetry; this difference, as I would add, in the representation of the two sexes continued to dominate the field of the visible for the next 500 years until the present. In her essay, coinciding with visual culture, Hammer- Tugendhat assumed that artistic modes of representation have an impact on society in general. She argued using the theories of Jacques Derrida, who suggested that the emergence and creation of difference conveys the potential to create identity [35].

According to the new mode of representation, persons assigned to the ‘woman’ category are shown in full corporal physicality and thus represent a material entity, whereas ‘men’ are depicted as immaterial or spiritual entities, such as golden light, rain or clouds. What I consider relevant for contemporary feminist discussions is that during the era when Jupiter’s adventures were first painted in large format (Danaë as painted by Titian or Artemisia Gentileschi and Io by Correggio), philosopher René Descartes (*1596 in La Haye en Touraine; † 1650 in Stockholm) outlined his influential theory. His principle, known as the mind-body dualism, describes a division between a material substance that extends in space, res extensa, and the immaterial spiritual or mental substance that has no expansive characteristic, res cogitans. Not only was Descartes’s design influential in the centuries to come, but his system was also repeatedly put into question. One critical voice had been that of Foster, who argued that ‘Cartesian perspectivalism’ results in the separation of subject and object, rendering the first transcendental and the second inert [36].

What is relevant for my study, is that the mind-body dualism is related to the bipolar coercive system of the sexes. As I have argued in another article on this topic, [37] in his writings, Descartes did not assign the ‘male’ entity to the immaterial res cogitans, nor did he establish a connection between the ‘female’ entity and the material res extensa [38]. However, as Butler claimed, a hierarchy arises when Descartes’s system is linked to twofold categorial thinking based on the ‘man’ and ‘woman’ division. The differentiation between the two substances, she argued, contains the tendency to be applied to other categories. Accordingly, the ‘mind’ is associated to ‘man’ and the ‘body’ with ‘woman’.

Thus, I conclude that the ‘male-female’ dualism closes out variations and turns a greyscale into a bipolar system of sexes. Moreover, following Butler, the mind-body dualism may also lead to a devaluation of ‘women’ because Western culture is characterised by a psychological and physical subordination of the ‘material principle’ associated with ‘women’ to the ‘spiritual’ and ‘rational’ principle associated with ‘men’ [39]. What is important for my argument is that in bipolar heteronormative thinking, categories such as ‘body’ and ‘mind’ are not merely conceived as different substances but involve a hierarchical relationship.

In the course of the 19th century, the mythological disguise of the love and sexuality scenes began to fade, starting with paintings such as Édouard Manet’s Olympia (1963) [40], in which he depicted Victorine Meurent, herself a highly talented young painter who exhibited her own work at renowned institutions, for instance, in the Paris Salon in 1876 [41]. Just like the works of her ‘female’ colleagues were not integrated in the high art canon, her works also found no collectors and therefore most of them are lost. The scandal of the Olympia painting consisted in the fact that Manet stripped the picture of its mythological narrative; Olympia/Meurent is directly looking at us, and some of the symbols surrounding her, such as the black cat standing in for promiscuity, make her readable as a prostitute [42] The servant, a person in the Black category, suggests the influence of the art history tradition of Danaë.

What Manet depicted, is a woman stripped bare of a mythological sphere. The images stemming from ancient Greek mythology were still influential throughout the 20th century [43,44]. In contemporary pop culture and the music industry, the absence of the ‘male’ part is still the dominant mode of representation in scenes of love and sexuality. In the mainstream music industry, there are innumerable examples of the asymmetry inherited from the Renaissance, with an absent ‘man’ representing an immaterial principle while the ‘woman’ is in full naked physicality. One example is the music video produced for the song ‘Partition’ (2013) by the singer and songwriter Beyoncé Knowles. With ancient Greek mythology in mind, the scene from minute 03:15 to 03:45 is readable as a re-enactment of the mythological tale of Jupiter and Io (Figure 6), as the ‘male’ part plays the role of the disembodied observer sitting in the front row of an auditorium while Beyoncé performs an erotic dance on stage – just for him. We can only guess the ‘male’ spectator’s features as he is enveloped in the smoke of his cigar, remaining invisible, whereas Beyoncé’s staging is characterized by hypervisibility, modulated against his obscurity.

It is interesting to note that in the video, the traditional roles of persons in the ‘black’ and ‘white’ categories are reversed. According to traditions in art history, in most pictures, Danaë is accompanied by a ‘black’ servant collecting coins that fall from the sky, as occurs, for instance, in Titian’s version of Danaë. By contrast, in Beyonce’s video (minute: 0:34), the servant belongs to the ‘white’ category. However, although the ‘black’ and ‘white’ positions are reversed, the hierarchy between ‘male’ and ‘female’ remains untouched.

In summary, a diachronic perspective allowed me to discuss in more depth performance and dance works, video art and music videos produced by the mainstream music industry. Having traced the genesis of the prevailing representations of love and sexuality, which are based on a physically present ‘female’ part and an absent ‘male’ part, I consider the strategy of the self-representation of nude or semi-nude ‘women’ on the stage of a theatre or in other public spaces to be a highly ambivalent endeavour. By referring to the naked ‘female’ body on stage, artists touch on a history of representation that has assigned a devaluated position to the to the ‘female’ part; thus, the prevailing order is involuntarily repeated. Following Schaffer’s methodology, in the next section, I will combine the diachronic perspective outlined so far with a synchronic perspective by turning to the contexts in which representations of love and sexuality appear.

Expanding to Create a Synchronic View

Having discussed who remains invisible and who is being-seen or given-seen on the theatre stage and in pictorial representations, I will now discuss the specific context in which certain artistic practices occur. At this point, I return to the non-authored example that I described in the mode of Mette Ingvartsen’s language choreography: a nude ‘woman’ alone on stage performing sexualized movements and, by doing so, enveloping herself in a cloud of white powder. From a diachronic perspective, this scene clearly becomes readable as a re-enactment of the story of Jupiter and Io. As this sequence that I once saw comes from contemporary theatre and performance, I will contextualize it by asking in which networks a contemporary dance and performance work can emerge nowadays. Asking about the context in which a work is seen may be a commonplace procedure for sociologists. In dance and theatre studies, however, this approach is rather rarely practiced. In English-language theatre discourse, sociologist and theatre scholar Rudi Laermans has pointed out that the usual focus of academics in dance studies is on the internal structure of a work, a procedure he called the single-work-centered approach [45]. Put differently, the concept of performance implies a methodological category for analysis. Drawing on Foster, I would even go so far to state that this methodological category, which theatre scholars obtain during their university education, shapes the process of seeing. Although Foster reminded us not to historicize the viewer too strictly in terms of cultural forms, [46] there is a noticeable tendency for theatre scholars to perceive dance and performance pieces as artefacts capable of unfolding distinct public spheres based on their internal aesthetic.

Consequently, the context in which works depicting love and sexuality appear remains unquestioned. To understand the networks and infrastructures in which a contemporary dance and performance work is embedded, it can be useful to digress to the era of postmodern dance. As Laermans pointed out, during the 1950s and 1960s, when experimental forms that would later be called postmodern dance began to emerge for instance, in the circles around the Judson Dance Movement based in New York – a dance market had not been established yet. Although there were visual arts galleries interested in unconventional hybrid formats based on a merging of dance and sculpture, besides small self-organized festivals and lofts run by artists themselves, there was no institutional network for distributing the works in a professional manner. An art market for dance performances that included institutions showing not only ballet or modern dance but also postmodern, modernist dance and experimental forms, such as conceptual dance, only emerged in Europe and North America in the early 1980s [47]. Like every infrastructure, this network provides both advantages and disadvantages. Artists and theorists have criticized the fact that since then, dance and performance pieces have become associated with income and profit and are thus evaluated by the number of visitors they attract [48]. The more spectacular a piece, the more spectators and the higher the profit – a simple formula that also propels voyeuristic formats.

At this point in the discussion, a sentence that Ingvartsen developed for her piece Speculations (2011) comes to my mind, as she tells the audience that our situation is ‘very different from the one that took place in the 1960s’ [49]. The dance market consisting of a network of theatres, renowned festivals and – as in the case of Beyoncé’s music video – music channels provides increased visibility and artists become famous as a result. Increased visibility provides its owner with what sociologist Pierre Bourdieu called prestige, or symbolic capital. Symbolic capital that entails certain dynamics, such as, again, an easier access to be-given-seen. However, there is a shadowy side to prestige and symbolic capital that involves repeating hierarchical orders. My argument is that the situation that has emerged against the backdrop of the dance and art market contains following problematic aspects. First, asymmetrical patterns and hierarchies are repeated – for example, the ‘female’ represents the body and the ‘male’ the mind. As the dance market immediately distributes these hierarchical and asymmetrical scopic regimes, the structures of the prevailing order receive no critical reflection and are merely channeled by a profit-oriented market addressing the audience and making money based on voyeuristic desires. Second, due to the fast network of distributive infrastructures, the artists in the ‘female’ category become visibly reduced and narrowed down to their bodies. At this point of the discussion the question arises whether there is a way out of the dynamics. Having discussed the context of the contemporary dance and performance field, in the last section, I will present works that foster variations in the field of the visual.

Expanding the Field of Possibilities

The search for variations – or, in Hal Foster’s words, ‘for alternative visualities’ [50] – and openings in constricted stereotypical representations, one of the reasons for writing this article, made me research artistic practices by artists such as Ingvartsen, to whose approach I attribute the potential to disturb prevailing structures of the visible. In her solo piece Speculations (2011), Ingvartsen referred to Yves Klein’s Anthropometries (1960-1962), which was based on a clear division between the ‘male’ and the ‘female’, with the ‘female’ performers in full nude physicality painting their bodies with blue paint (Yves Klein’s patented Blue) and pressing themselves on white canvas, while the ‘male’ artist remained outside of the main scene. Through her strategy of making the performative event happen at an imaginary level, Ingvartsen involves her spectators in a very specific way, as she kindly asks them to find a person in the audience with whom they feel comfortable and to imagine this person being naked. She goes on to encourage the audience to imagine this person covering him- or herself with paint (in her piece, the colour of the paint is metallic, not blue) [51] The gesture of asking the spectators, who are to be called listeners, to imagine a person with whom they feel at ease involves a greyscale of appearances and social positions. Using words, Ingvartsen not only brings the ‘male’ back; more than this, she opens up the field of the visible and the thinkable in a profound way.

In the contemporary dance and performance field, there are innumerable examples that cross out or at least shift the prevailing modes of representation. Having the Middle Ages bath scene from the aforementioned Factorum ac dictorum memorabilium libri IX in mind, a performance by artist and curator Satu Herrala caught my eye. Her project called Sauna Lectures premiered in 2011 at Spielart Festival in Munich. By having the audience sit in a sauna (following the rules of particular saunas, either in swimwear or naked), the audience was made up of equal bodies sharing space. In this more than unconventional setting, Herrala invited theorists to discuss socio-political issues together with the audience. As Herrala told me, it was her intention to flatten some of the hierarchies that can be found in Western societies [52]. One of the boundaries the work crossed was that between the rich and the poor as expressed by clothes. In my reading, the work also touches on another demarcation line, namely that between the ‘male’ and the ‘female’ and the inequalities conveyed by traditional depictions. My argument is that Herrala’s project deconstructs the ‘male’ and ‘female’ separation as well as the body-mind-dualism, as both parts were physically present and addressed by theorizing certain issues together.

A further aspect that I perceive as highly relevant is that in the context of Sauna Lectures, there were no passive spectators. The people who paid for the admission were also invited to actively participate in the discussions, an aspect that makes me read the work as immersive theatre. It was this notion that prevented Herrala from producing video documentation, as this would have reinstalled the subject-object division between spectators sitting in front of screens and those who were actively involved. Accordingly, Sauna Lectures succeeded in creating a sphere in which divisions were deconstructed at several levels and in which conventional representations and social orders were opened up, with the bipolar system of the sexes being one of these lines crossed by the work.

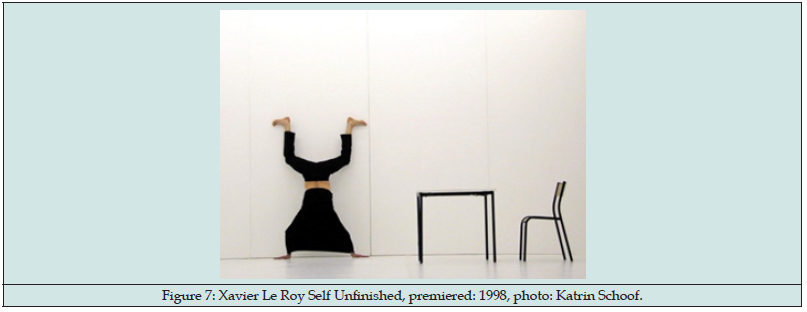

With the piece Self Unfinished (1998), the French choreographer Xavier Le Roy pursued a completely different strategy challenging the bipolar system of the sexes. Although this performance adhered to the traditional theatre order, with the performer Le Roy separated from his audience on stage, the performance critically tested the audience’s perception. The title of the piece is already readable as an expression of Le Roy’s non-essentialist thinking; in fact, while developing the piece, Le Roy read Judith Butler’s Gender Trouble extensively [53]. A simple costume and many rehearsals were necessary to create spectacular body configurations aimed at distorting the audience’s perceptions. The costume, a narrow tube-like shape coloured in black, served to partially cover Le Roy’s body; pulled over his head as he bent forward, it was impossible for me as a spectator to distinguish his legs from his feet and to clearly identify individual body parts. He seemed to dance with himself – a headless cephalopod. With this form of staging, Le Roy succeeded in making the upper and lower parts of the performed figures indistinguishable. Theatre scholar Gerald Siegmund once discussed this work through the lens of the theory of absence as elaborated by him and concluded that Le Roy’s work opens up the field of appearances through the absence of clearly distinguishable semantic patterns [54]. According to my reading, this work breaks up the dualistic system of the sexes through the lack of a form that could be interpreted using the ‘male-female’ scheme.

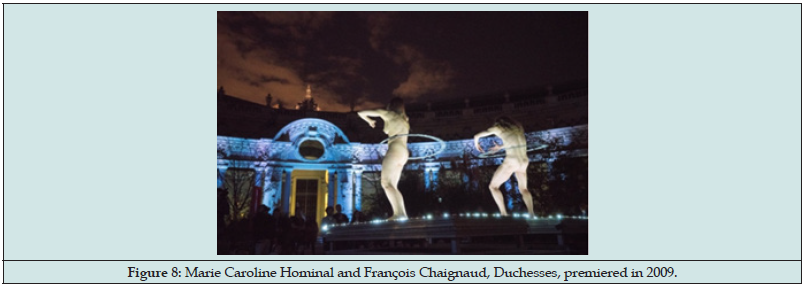

Both examples, Sauna Lectures by Satu Herrala and Self Unfinished by Le Roy, disturb social roles and their legibility by bringing back the ‘male’ body as a physical, corporeal entity. Duchesses (2009), a piece by Marie Caroline Hominal and François Chaignaud, which I saw in the baroque gardens of the Belvedere in Vienna in 2012, played with depictions of the sexual act. Chaignaud and Hominal were standing in bare corporeality side by side on pedestals that were lit from below. The task of holding a hula hoop at constant height around the pelvis created slightly wavy movements that stood in contrast to the mineralised stillness of the baroque sculptures of the Belvedere garden. Although Hominal and Chaignaud did not touch each other a single time during the performance, which lasted approximately 40 minutes, the sexual act ‘happened’. It happened at an imaginary level in the spectators’ minds, as the naked rhythmic movements were reminiscent of the rhythm that unfolds in the act of love and sexuality.

The selection of some examples from the field of dance and performance is an extract of a whole range of contemporary artistic practices meant to disturb and expanding our manner of seeing. These works, which provide spectators with alternative visualities, may be seen as an indication that critical analysis of and discussion on traditions is a necessary undertaking if prevailing orders in the field of the visual are to be opened up in a profound way. My point is that a change in social order and a flattening of hierarchies can only happen, and people in the ‘women’ category can strengthen their voices in public, by introducing variations in the field of the visual and breaking up common patterns. It is surely not sufficient to display the naked body in a way that uncritically and perhaps unconsciously repeats established hierarchies.

References

- Schaffer Johanna, Ambivalenzen der Sichtbarkeit. Über die visuellen Strukturen der Anerkennung, Bielefeld: transcript Verlag 2008, p. 12; Schaffer refers to Schade Sigrid / Wenk Silke: Inszenierungen des Sehens. Kunst. Geschichte und Geschlechterdifferenz in den Kulturwissenschaften, Stuttgart: Körner 1995, p. 343 and Schade Sigrid / Wenk Silke, Strategien des ‘Zu-Sehen-Gebens’. Geschlechterpositionen in Kunst und Kunstgeschichte, in: Bußmann Hadumod / Hof Renate (eds), Genus. Geschlechterforschung/Gender Studies in den Kultur- und Sozialwissenschaften, Stuttgart: Körner 2005.

- Informed by sociology, I perceive the performer, although singularis, ed by media reports, theatre houses and festivals, as located in a field of pressure between the concrete expectations of responsible persons (e.g. theatre directors) and the logics of turbo-capitalism; for an example of the media reports, I am referring to Tanz. Eine Sylphidische Träumerei in Stunts, one of the most successful contemporary pieces, see: Florentina Holzinger im Gespräch mit Janis El-Bira, in: Deutschlandfunk Kultur, published: 15. February 2020, weblink: https://www.deutschlandfunkkultur.de/performerin-florentina-holzinger-fuer-diese-show-lernen-wir-100.html (last accessed: June 28 2022).

- Phelan Peggy (1993) Unmarked: The Politics of Performance, London, New York: Routledge p. 10; cited in Schaffer, Ambivalenzen der Sichtbarkeit p. 15.

- Becker Ilka (2014) Gender und Repräsentationskritik, in: Butin, Hubertus (ed.), Begriffslexikon zur zeitgenössischen Kunst, Köln: Snoeck 98.

- (2020) See, for example: Wihstutz Benjamin / Hoesch Benjamin (eds), Neue Methoden der Theaterwissenschaft, Bielefeld: transcript Verlag 2020 and Balme Christopher / Szymanski-Düll Berenika (eds), Methoden der Theaterwissenschaft. Forum Modernes Theater, Bd. 56, Tübingen: Narr Francke Attempto.

- (1998) Visual culture theorist Mirzoeff defends the concept of ‘visual culture’ as a designation for a research practice that does not entail the separation between critique/theory on the one hand and practice on the other, as ‘visual studies’ do; see: Mirzoeff Nicholas, The Subject of Visual Culture, in: idem (ed.): The Visual Culture Reader, London Routledge, New York, USA.

- Holert Tom (2005 ) Kulturwissenschaft/Visual Culture. Sachs-Hombach, Klaus (ed.) Bildwissenschaft. Disziplinen, Themen, Methoden, Frankfurt am Main: Verlag Peter Lang pp. 226-235.

- Mitchell WTJ (2002) Showing Seeing: A Critique of Visual Culture, in: Holly Michel Ann / Moxey Keith (eds): Art History, Aesthetics. Visual Studies, Yale University Press: New Haven pp. 231-250.

- Foster Hall (1988) Preface idem (ed.), Vision and Visuality, New York: The New Press 1999, first published: Bay Press p. XIII.

- Butler Judith (1990) Gender Trouble, New York (et. al.): Routledge.

- Becker, Gender und Repräsentationskritik p. 97.

- Butler, Gender Trouble pp. 22-34.

- Butler, Gender Trouble pp. 22-34.

- My writing style is an expression of non-essentialist thinking. By using quotation marks, I intend to underline the way in which categories shape our thinking.

- Foster, Vision and Visuality pp. IX–XIV.

- Schor Gabriele, “Ich möchte hier raus!“ Birgit Jürgenssens Kunst der 1970er Jahre, in: idem / Rorro, Angeladreina (eds): Feminist Avant-Garde of the 1970s from Sammlung Verbund, Galleria nazionale d‘arte moderna: Exhibition Catalogue, Rome 2010, pp. 196–213, weblink: https://birgitjuergenssen.com/bibliographie/texte-essays-interviews/ich-moechte-hier-raus-birgit-juergenssens- kunst-der-1970er-jahre (last accessed: July 1, 2022).

- Website, link: https://birgitjuergenssen.com/werke/fotos/ph17 (last accessed July 26, 2022)

- Foster, Vision and Visuality, p. IX.

- Schaffer, Ambivalenzen der Sichtbarkeit.

- Schaffer, Ambivalenzen der Sichtbarkeit p. 12.

- Schaffer is considering theories by Silke Wenk and Sigrid Schade; see: Schade / Wenk, Inszenierungen des Sehens p. 343.

- Schaffer Ambivalenzen der Sichtbarkeit p. 12 and p. 33

- Lepecki André, Singularities. Dance in the Age of Performance, London and New York: Routledge 2016, p. 66.

- Lepecki, Singularities p. 68.

- Hammer Tugendhat Daniela (1994) Erotik und Geschlechterdifferenz. Aspekte zur Aktmalerei Tizians, in: Erlach Daniela / Reisenleitner,Markus / Vocelka Karl (eds), Privatisierung der Triebe? Sexualität in der Frühen Neuzeit, Vol. 1, Frankfurt am Main: Verlag Peter Lang 367-446.

- Website, link: https://nl.wikipedia.org/wiki/Factorum_ac_dictorum_memorabilium_libri_IX (last accessed July 1, 2022).

- Hammer-Tugendhat, Erotik und Geschlechterdifferenz pp. 371-372.

- Pope Clement VII burned and prohibited a series of woodcuts desirous ‘men’ side by side with the ‘female’ part. The graphic artist Marcantonio Raimondi was sentenced to prison, and any further distribution of these images was punishable by death; see: Hammer-Tugendhat, Erotik und Geschlechterdifferenz pp. 390-394.

- Ovid 1994.

- Website, link: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Danae_(Artemisia_Gentileschi) (last accessed July 3, 2022).

- Website, link: https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Datei:Tizian_-_Danae_receiving_the_Golden_Rain_-_Prado.jpg (last accessed July 3, 2022).

- Ovid (P. Ovidius Naso), Metamorphosen libri quindecim. transl. by v. Albrecht Michael von. Stuttgart: Reclam 1994, liber quartus (IV, 610-613) pp. 216-217.

- Ovid, Metamorphosen, liber primus (I, 713–750) pp. 57–59.

- Website, link: https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jupiter_und_Io (last accessed July 18, 2022).

- Derrida Jacques (1967) Of Grammatologie, transl. by Spivak Gayatri Chakravorty, Baltimore and London: The John Hopkins University Press 2003; De la grammatologie, Paris: Minuit.

- Foster, Vision and Visuality p. X.

- Julian Iris, The Absent Man. In Depictions of Love and Sexuality, written in 2021, still in the Peer-Review Process, to be published in 2022.

- Upon a closer look at Descartes’s life, which can be traced through documents, reveals the ‘women’ who influenced his thinking. In his Meditationes de Prima Philosophia (1641), Descartes addressed the audience imagined as ‘man’ with the Latin term ‘vir’, but as philosopher Peter Prechtl mentioned, Descartes had two ‘female’ friends. In 1642, he began to exchange letters with countess Elisabeth von der Pfalz. She made critical remarks on his dualism of substances, as she questioned whether an immaterial soul could actually have an effect on the body. In 1647, Descartes established close contact with the queen of Sweden, Christine, who wanted to turn Stockholm into an intellectual centre. Communication with Christine and Elisabeth influenced the development of Descartes’s theories; see: Prechtl Peter, Descartes. Zur Einführung, Hamburg: Junius 2000 pp. 27–28.

- Butler, Gender Trouble p. 17.

- Website, link: https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Olympia_(Gemälde) (last accessed July 23, 2022)

- Dictionnaire général des artistes des l’École française depuis l‘origine des arts du dessin jusqu’à nos jours : architects, peintres, sculpteurs, graveurs et lithorgraphes, Gallica Bibliothèque nationale de France, p. 80, weblink: https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k113384f/f81.image.r=meurent.langFR (last accessed July 24, 2022)

- Clark Timothy, J., The Painting of Modern Life: Paris in the Art of Manet and his Followers, London: Thames and Hudson 1984.

- As described in my MA thesis, in the 1970s, ‘female’ video artists such as Ulrike Rosenbach and VALIE EXPORT experimented in the video medium with superimpositions of their own images and images as found in art history based on their research on roles and gestures, see: Julian Iris (formerly Gütler), Strategien der Identitätssuche in den Performances von Ulrike Rosenbach, MA thesis, Vienna: University of Vienna 2005 pp. 34-48.

- Website, link: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=pZ12_E5R3qc (last accessed July 2, 2022).

- Laermans Rudi, Moving Together. Theorizing and Making Contemporary Dance, Amsterdam: Antennae Valiz 2015, pp. 24-25; new approaches in theatre sciences have broadened established views by referring to the social sciences, see Whistutz / Hoesch (eds), Neue Methoden der Theaterwissenschaft 2020.

- Foster, Vision and Visuality, p. XI.

- Laermans, Moving Together pp. 17–21 and pp. 60–63.

- Husemann, Pirkko, Choreographie als kritische Praxis. Arbeitsweisen bei Xavier Le Roy und Thomas Lehmen, Bielefeld: transcript Verlag (Reihe TanzScripte) 2009.

- Lepecki, Singularities p. 68.

- Foster, Vision and Visuality p. XIV.

- Lepecki, Moving Together p. 68.

- We communicated via digital services on 22 June 2022.

- Julian Iris, Formen der Zusammenarbeit und des “Mit-Seins“. In Projekten der darstellenden und der bildenden Kunst, Vienna: Academy of Fine Arts 2021 pp. 19-21.

- Siegmund Gerald, Abwesenheit. Eine performative Ästhetik des Tanzes. William Forsythe, Jérôme Bel, Xavier Le Roy, Meg Stuart, Bielefeld: transcript Verlag 2006 pp. 371-374.

Top Editors

-

Mark E Smith

Bio chemistry

University of Texas Medical Branch, USA -

Lawrence A Presley

Department of Criminal Justice

Liberty University, USA -

Thomas W Miller

Department of Psychiatry

University of Kentucky, USA -

Gjumrakch Aliev

Department of Medicine

Gally International Biomedical Research & Consulting LLC, USA -

Christopher Bryant

Department of Urbanisation and Agricultural

Montreal university, USA -

Robert William Frare

Oral & Maxillofacial Pathology

New York University, USA -

Rudolph Modesto Navari

Gastroenterology and Hepatology

University of Alabama, UK -

Andrew Hague

Department of Medicine

Universities of Bradford, UK -

George Gregory Buttigieg

Maltese College of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Europe -

Chen-Hsiung Yeh

Oncology

Circulogene Theranostics, England -

.png)

Emilio Bucio-Carrillo

Radiation Chemistry

National University of Mexico, USA -

.jpg)

Casey J Grenier

Analytical Chemistry

Wentworth Institute of Technology, USA -

Hany Atalah

Minimally Invasive Surgery

Mercer University school of Medicine, USA -

Abu-Hussein Muhamad

Pediatric Dentistry

University of Athens , Greece

The annual scholar awards from Lupine Publishers honor a selected number Read More...